How Illinois can lower its sales tax rate & raise funding for transit

By Chrissy Mancini Nichols

Aug 20, 2014

This post first appeared at metroplanning.org

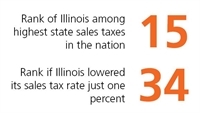

The State of Illinois’ 6.25 percent sales tax is among the highest levied by any state. With local sales taxes factored in, Chicago tops the list of large cities’ combined sales tax rates, an ignominious ranking that it shares with Los Angeles. But Illinois could lower its sales tax rate and still raise needed revenue, making the state more attractive to business while giving low- and middle-income populations tax relief. In fact, the state could reduce the rate by as much as one percentage point, and still take in more revenue.

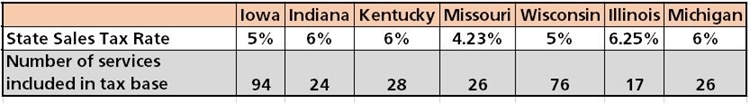

How? By strategically expanding the tax to include personal services. Illinois’ sales tax base (the types of goods and services taxed) has not been updated since the tax was first adopted in 1933, and it remains one of the narrowest sales tax bases in the country: Only 17 of 168 potential taxable services are included. Illinois’ sales tax base is narrower than all of its neighboring states, and it is the fourth narrowest in the country.

History of the sales tax

The sales tax was first introduced by states during the Great Depression. At the time, states and localities received most of their revenues from property taxes. As property values began to collapse, states had to look to other sources of revenue to continue paying for infrastructure and essential services, leading to the adoption of the sales tax. States focused their sales tax bases on tangible goods such as clothing, which made sense in an economy based mostly on goods.

Since that time, the service sector has grown dramatically, and now accounts for two-thirds of the nation’s economy. However, the Illinois sales tax remains based on declining goods spending.

The State of Illinois’ 6.25 percent sales tax is among the highest levied by any state. With local sales taxes factored in, Chicago tops the list of large cities’ combined sales tax rates, an ignominious ranking that it shares with Los Angeles. But Illinois could lower its sales tax rate and still raise needed revenue, making the state more attractive to business while giving low- and middle-income populations tax relief. In fact, the state could reduce the rate by as much as one percentage point, and still take in more revenue.

How? By strategically expanding the tax to include personal services. Illinois’ sales tax base (the types of goods and services taxed) has not been updated since the tax was first adopted in 1933, and it remains one of the narrowest sales tax bases in the country: Only 17 of 168 potential taxable services are included. Illinois’ sales tax base is narrower than all of its neighboring states, and it is the fourth narrowest in the country.

History of the sales tax

The sales tax was first introduced by states during the Great Depression. At the time, states and localities received most of their revenues from property taxes. As property values began to collapse, states had to look to other sources of revenue to continue paying for infrastructure and essential services, leading to the adoption of the sales tax. States focused their sales tax bases on tangible goods such as clothing, which made sense in an economy based mostly on goods.

Since that time, the service sector has grown dramatically, and now accounts for two-thirds of the nation’s economy. However, the Illinois sales tax remains based on declining goods spending.

A fairer tax

If properly designed, sales taxes play a crucial role in a state’s balanced tax system. To be well-designed, most economists believe a sales tax must be broadly defined to capture an accurate snapshot of consumer spending. By applying sales tax to what consumers actually spend, the sales tax becomes a less volatile and more stable revenue source. If the Illinois sales tax was updated to match consumer spending, lawmakers could reduce the state rate and take in more revenue over time. As consumers continue to spend more on services, revenues will continue to grow. Struggling localities and mass transit agencies that rely on sales tax revenue to cover daily operating expenses also would see an immediate benefit.

Expanding the sales tax base and reducing the rate creates a fairer tax. By exempting services from the tax base today, Illinois discriminates against buyers who consume more goods, violating the principle of “horizontal equity.” For example, a low-income individual is more likely to buy a lawn mower to cut his own grass, while a wealthier person is more likely to hire a landscaping service. The lower-income person pays a tax on the mower, while the wealthier person pays no tax on the service. Including services in the state’s sales tax base concurrently with a rate reduction would result in a tax break for those consumers who purchase more goods than services.

Other states with narrow tax bases have begun to shift to services. Maine and Connecticut, in 2009 and 2011, respectively, updated their sales taxes to include personal services such as manicures, pet grooming and dry cleaning.

Expanding the base, lowering the rate in Illinois

Expanding the current Illinois sales tax base to include consumer services (but not business, health care or housing services), combined with a 1 percent reduction in the state sales tax rate (to 4.0 percent), would generate the following additional revenue:[1]

Even with a 1 percent sales tax rate reduction, updating the sales tax to include personal services would generate a significant amount of revenue that could both serve as a stabilizing operating stream for state and local governments and generate dollars for new and improved transit service, such as Bus Rapid Transit. Because the services sector will grow more rapidly, it will generate more revenue in the long term, even with the rate reduction.

Broadening the sales tax base and reducing the rate is a logical step. It would support state and local governments and transit agencies across Illinois, and reduce taxes for middle- and low-income groups, securing Illinois’ economic future.

——

[1] Revenue estimates based on comparison data from the Federation of Tax Administrators, State Sales Taxation of Services, July 2007, in conjunction with state and county receipt data from the 2007 Economic Census updated to 2013 using the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index yearly average. The estimate was then refined to exclude business-to-business transactions following a similar model used by the Illinois Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability (CGFA), using the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ national input-output models to calculate the percentage of an industry’s outputs that went to final users, not intermediate production. Revenue loss from a one percent state sales tax rate cut calculated using final fiscal year 2013 Illinois Government Office of Budget and Management General Fund sales tax revenue figures.