Americans live farther away from their jobs, burdening lower-income workers

By Chrissy Mancini Nichols

Apr 14, 2015

This post first appeared at metroplanning.org

New analysis from Elizabeth Kneebone and Natalie Holmes of Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program finds that between 2000 and 2012, in the nation’s most populous metros, private sector jobs moved farther away from where people live, especially in the suburbs and in low-income communities. Using a typical commute distance factor, overall, between 2000 and 2012, in the 96 major metro areas in the U.S. the number of jobs where people live fell by 7 percent.

Overall trends

Of the 96 metros studied, only 29 increased the number of jobs close to a typical resident. In 37 metros, overall employment increased but the number of jobs close to where people live declined, suggesting that employment location decisions did not take into account where people actually reside. Most types of jobs should locate near dense areas of population to increase transportation options for commuters and reduce commute times—resulting in less automobile congestion and reliance on fuel and more leisure time for people. Locating jobs close to where people live also helps low-income residents in overcoming transportation and childcare hurdles when pursuing employment opportunities.

In metropolitan Chicago, between 2000 and 2012 the number of jobs within the typical commute distance, which Brookings defines as 10 miles in Chicago, fell by 14 percent. Of the 96 metros studied, the Chicago metro ranks 85th in the growth in number of jobs near the typical resident, tied with Birmingham, Alabama, and Akron, Ohio.

The study also broke out job growth by city and suburban locations. In the 96 metros, the overall number of jobs in cities fell by 2 percent, while the number of jobs in the suburbs rose by 4 percent during the time period. However, because job density declined in the suburbs, the typical city resident lives closer to three times as many jobs on average as the typical suburban resident. In the Chicago metropolitan area, the overall number of jobs in both the suburbs and cities declined. However, due to suburban sprawl, the change in the number of jobs close to people in the suburbs declined by 15 percent, almost twice the 8 percent decline for city residents—those living in Chicago, Naperville or Elgin.

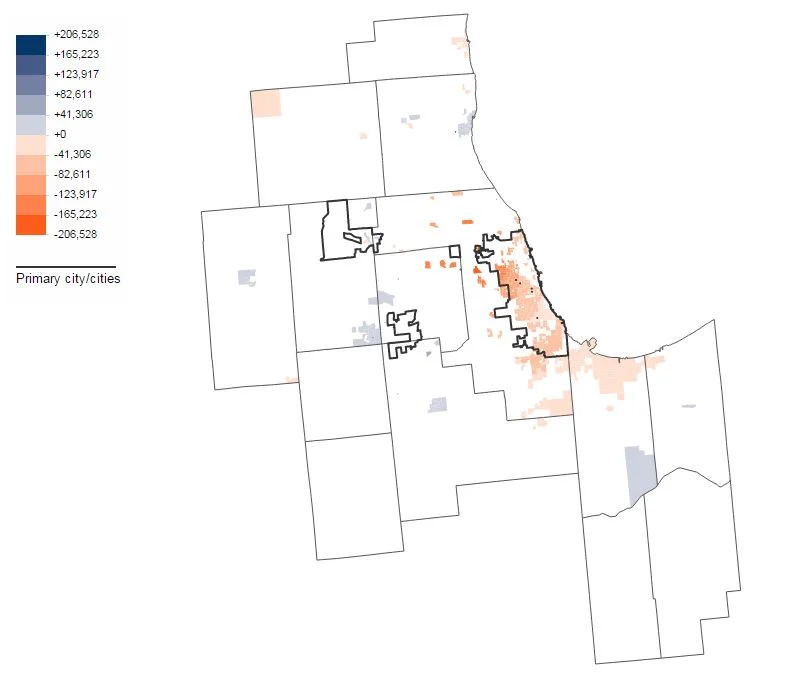

Chicago region: Percent change in the number of jobs within a 10-mile commute, 2000-2012

Source: The Brookings Institution

While overall Chicago metro area residents saw their proximity to jobs decline, not so for those living in the far western suburbs, where the number of jobs near residents increased, mirroring growing transportation and logistics employment clusters. Jobs decreased at higher rates for inner-ring suburbs and the far South Side of the City of Chicago.

Chicago region: Change in the number of jobs within a 10-mile commute in high poverty communities, 2000-2012

Source: The Brookings Institution

Kneebone and Holmes write that, “…where people live and where jobs locate within a metro areas makes a difference…” adding, “The way those patterns shift across places over time can create winners and losers in a metro area…even in metro areas that perform well on overall growth measures.”

This calls for regions to work together on economic development strategies. A solution from the Minneapolis region—one of the most economically prosperous in the U.S.—is the Fiscal Disparities Act, which enables Minneapolis to avoid the lose-lose habit of giving away tax revenues to lure businesses to move around in the region without overall net job growth.

The data also proves the need to locate jobs in densely populated areas close to transit so people have more access to jobs and options for commuting. The Metropolitan Planning Council is working on expanding housing opportunities and transportation options in low-poverty, opportunity communities through the Regional Housing Initiative and Voucher Pilot, and on building municipal capacity to address the suburbanization of poverty and housing market instabilities, an initiative highlighted in the Brookings recommendations. These will forward regional planning goals included in Chicagoland’s comprehensive growth plan, GO TO 2040. Together they will prioritize housing and transportation policies and investments region-wide to align with economic development goals, ensuring sustainable growth that provides residents employment, transportation and housing options.