A New Way of Doing P3s for social infrastructure in Illinois

By Chrissy Mancini Nichols

This post first appeared in the August 2015 issue of Government Finance Review, a journal of the Government Finance Officers Association.

The State of Illinois, and particularly the Chicago region, is facing mounting modernization needs. In 2013, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave infrastructure in Illinois a grade of C- and estimated the total cost of urgently needed repairs at $100 billion – five times the state’s total fiscal 2015 capital budget. Dramatic examples such as buckling floors at the Joliet Courthouse and a crumbling overpass at Belmont and Western avenues in Chicago underscore the consequences of allowing infrastructure investment to lapse.

Investing in infrastructure is critical, not only to maintain safe and reliable roads, public transit, water mains, and sewer lines, but also to expand the economy. Growth depends on the pipes under the streets not leaking as they carry clean water. Downtown areas need to be revitalized to attract and retain new businesses and reduce traffic and commute times. Repairs and new capital investments are not an either/or proposition – pursuing both aggressively and transparently is the ticket to economic growth.

EXPLORING NEW OPTIONS

From city and state transportation agencies to municipalities, governments across the country are working to identify better and faster ways to serve residents by delivering infrastructure projects. The playing field is far from level. While some governments have the expertise to wade into new and complex financial transactions, many others are fiscally stressed and/or are still getting up to speed.

In 2014, the Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) co-hosted a forum with the Metropolitan Mayors Caucus called “Breaking New Ground: Innovative Financing Strategies for Municipal Projects.” Designed to provide information about financing municipal infrastructure with private investment, the forum brought together municipal leaders and investment experts to explore an important pathway to funding: collaboration.

THE P3 PATH

MPC introduced municipalities to the public-private partnership (P3) option, soliciting community projects before the event to use as potential case studies during the forum. Most of the submissions were for public buildings or water and sewer infrastructure – projects with price tags between $350,000 and $5 million. MPC’s financial experts felt that larger projects, more on the scale of the $3 billion Elgin O’Hare Western Bypass or the privatization of Midway Airport, make more sense for P3s.

The forum pinpointed a communication gap between the private and public sectors and the opportunity for communities to aggregate common needs that may otherwise be too small to implement via nontraditional delivery. Communities that wish to pursue a P3 should be aware that differences in communication and expertise are key barriers to tapping private investment at the local level, creating an increased risk of transaction failures. Collaborative thinking and communication is best accomplished through coordination at a regional scale. To facilitate this municipal coordination and bridge the gap between the public and private sectors, MPC believes an infrastructure intermediary is the solution.

An Infrastructure Intermediary

MPC advocates the creation of Infrastructure Illinois (I2), an intermediary that would identify better and faster ways to deliver infrastructure solutions in the region – and ultimately create a replicable standard for project delivery across the United States. MPC’s role is to advise on the intermediary structure, help overcome policy and legal challenges, and broker relationships with local governments and other potential customers.

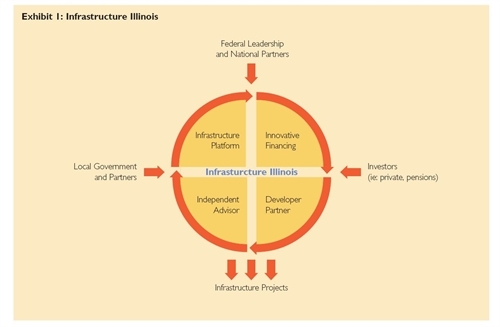

Success stories from Canada and Australia have shown that infrastructure intermediaries can reduce cost, increase competition and competently deliver projects. (See Exhibit 1.) Working with local units of government, I2 will identify P3 candidates and build a project pipeline. By standardizing and streamlining the evaluation, procurement and oversight processes, the intermediary establishes one replicable framework. The intermediary also acts as an expert and negotiator on behalf of the public sector to serve public priorities. The intermediary will thus create an open and fair marketplace more conducive to high-quality, competitive infrastructure investments.

Critically, this “for government, by government” entity would have the necessary skill sets to evaluate the value for money of entering into a P3 compared with a traditional delivery method; negotiate and manage a competitive bid process, with a goal of getting the best deal; allocate risk; and deliver projects quicker and cheaper. It would also monitor implementation and analyze return on investment. Illinois is well positioned to make progress and to create a pilot for broader application.

Instead of creating more units of government, MPC is working with existing local and state agencies such as the Public Building Commission (PBC), Capital Development Board (CDB) and Illinois Finance Authority (IFA), existing bodies that are respected and well positioned with the skill sets necessary to serve as the intermediary. (See Exhibit 2.) It can be advantageous for municipal governments to work with nonprofit public entities formed under the Illinois Public Building Commission Act1 in implementing projects. Unlike governments, which may build a public building once every few decades, ramping up staff and capital only when necessary, the core mission of these entities is to build infrastructure.

The PBC and CDB are construction experts with the legal authority to work throughout the state. They can leverage other sources of financing, and the PBC, thanks to its long track record, can make building and maintaining infrastructure more efficient. PBC has a broad range of powers such as to design, build, finance, operate and maintain infrastructure, as well as eminent domain and bonding authority. These entities have built schools, libraries and other public buildings throughout the state.

Likewise, the IFA is a statewide financing and procurement conduit that works with local governments on financing, evaluating, and negotiating project terms. It has issued, on average, $2 billion in bonds annually. The IFA, PBC and CDB have established private- and public-sector reputations, which is crucial for an intermediary’s success.

Aggregating Projects

Infrastructure Illinois would also facilitate collaboration and aggregation. This is vitally important since the Chicago region has 284 municipalities (more than any other in the country). That means it has more police and fire stations and town halls, and more entities building and repairing water mains. Projects tend to be smaller in cost, so if a municipality wants to consider the P3 option, one way to access private investors is through aggregation of projects.

Private infrastructure investors have a minimum threshold of about $20 million. To meet that threshold, aggregation—or bundling—of projects is necessary to access private capital and could result in cost savings to boot. If, for example, several municipalities needed to build a police station, they would work together on financing, construction timelines, procurement and even project delivery, realizing savings by using a single point of entry for implementation.

Aggregation of projects makes sense because the economy doesn’t follow political boundaries. In an era of declining fiscal support from the federal and state governments, communities can better accomplish goals if they work with one another. Cooperating to achieve efficiencies is not a new idea for municipalities; for instance, neighboring communities often contract with the same water provider or garbage collector to secure a lower cost. However, collaboration for infrastructure projects is relatively untested – and metropolitan Chicago has become a national proving ground for this approach. Since 2009, 23 suburbs in south Cook County have been working together to advance jointly adopted redevelopment, as well as more efficient and effective housing and community development strategies.

Illinois offers many legal paths to allow for the aggregation of projects. Article VII, Section 10, of the Illinois Constitution allows units of local government to work together and even encourages collaboration. It does so through the Intergovernmental Cooperation Act. The act grants public agencies the authority to combine powers to perform services. Similarly, the Governmental Joint Purchasing Act allows agencies to join powers to make bulk purchases of supplies and services.

Lifecycle Costs

When building infrastructure, capital costs are often the only consideration. A building will gradually decline, and the municipality must perform capital work, which is disruptive, expensive, and often not budgeted for at the outset. While P3 implementation might mean higher upfront capital costs, municipalities can transfer risk to the private sector for the long-term operations costs, resulting in lower total life cycle costs of the asset. (See Exhibit 3.) Under a P3 structure, operations costs are determined upfront. Regular preventative maintenance is scheduled, making for a stable, planned budget and a better-maintained building. It also can save municipalities money in the long term by mitigating costs caused by a disaster. For example, if a building floods, the private sector is responsible for covering the costs. The intermediary would evaluate all of these costs to determine the appropriate delivery method.

Skillful negotiation, proper financing incentives, and transparency are the necessary ingredients to bring the best infrastructure projects to market with expediency and cost controls.

NATIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE

A solution for our national infrastructure will likely require both federal leadership and complementary regional efforts. I2 may serve as a template for one key component of a national solution.

Federal Leadership. On July 17, 2014, President Obama announced the Build America Investment Initiative, including a national knowledge center to support state and local governments that want to harness the potential of alternative capital to complement traditional infrastructure funding. The Build America Transportation Investment Center is a great start to providing local assistance on P3 projects. There may be additional benefits to expanding the Center’s role to include key project priorities and guidance. This provides direction to local and regional efforts and communicates to the private sector important information about the projects.

In his 2015 State of the Union address, President Obama proposed a Qualified Public Infrastructure Bond (QPIB) program that would expand the existing Private Activity Bond program to allow for a cheaper way to finance projects for solid waste disposal, sewer, water, and other transportation projects. There would be no limit on how many QPIBs governments can issue annually, and the bonds would have no expiration date.

Local Efforts. Financial support for regional and local efforts will also be valuable in spurring private capital investment. Existing tools such as the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) and the new Water Infrastructure Finance Innovation Authority have already triggered significant private investment for transportation and, now, water projects. Creation of TIFIA-like funds for social infrastructure will need to expand the impact of a proven model. Also, greater flexibility in allocating existing resources may help to jumpstart P3s, such as administrative support for P3 intermediaries such as I2.

Third-Party Evaluation: A Case Study

In 2008, a private-sector firm leased Chicago’s downtown parking meters for $1.15 billion for a 75-year concession, the first privatization of an urban parking meter system in the United States. Many call the Chicago parking meter concession a failed P3, rushed through to fill budget holes in the short term without consideration for the detrimental impacts on taxpayers over the next seven decades. The city was willing to give up significant rights to the asset in order to reduce its debt instead of making a long-term investment that would have generated economic returns.

The lesson? Privatization agreements acting in the public interest should be subject to an independent third-party review. Because P3s are highly complex, an independent third party should serve as a proxy for the public to ensure its interests are protected. An independent body with the authority to review concession documents from the citizen’s perspective and look for inconsistencies between the agreement and current and future taxpayer needs is essential. The city council also benefits from an independent report on the transaction’s parameters.

CONCLUSIONS

Municipalities must think differently about their capital plans. Taking a new approach to planning and building infrastructure can open doors to new capital markets, save money, and fundamentally change how we invest in infrastructure to deploy new financing tools when appropriate, creating a replicable standard for local governments across the country. Modernizing local government’s aging infrastructure will put the nation back on the path of economic growth.

Note

The Public Building Commission of Chicago was organized under the Public Building Commission Act passed by the Illinois State Legislature in 1955, providing that any county or county seat in the state may organize a Public Building Commission, with the power to issue revenue bonds for the construction of government buildings.

Third-Party Evaluation: A Case Study

In 2008, a private-sector firm leased Chicago’s downtown parking meters for $1.15 billion for a 75-year concession, the first privatization of an urban parking meter system in the United States. Many call the Chicago parking meter concession a failed P3, rushed through to fill budget holes in the short term without consideration for the detrimental impacts on taxpayers over the next seven decades. The city was willing to give up significant rights to the asset in order to reduce its debt instead of making a long-term investment that would have generated economic returns.

The lesson? Privatization agreements acting in the public interest should be subject to an independent third-party review. Because P3s are highly complex, an independent third party should serve as a proxy for the public to ensure its interests are protected. An independent body with the authority to review concession documents from the citizen’s perspective and look for inconsistencies between the agreement and current and future taxpayer needs is essential. The city council also benefits from an independent report on the transaction’s parameters.